National Treasure: Barnaby Faull

Country Gentleman's Association Magazine Feature:

A Gentleman of Note

|

Established in 1666 Spink of London have long been associated with the trade in ancient and rare coins. They also deal in the world's most desirable banknotes under the knowledgeable eye of Barnaby Faull

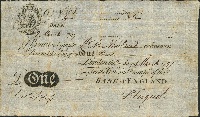

If you should come across an eighteenth century Bank of England banknote in the back of an old drawer somewhere, you will be pleased to hear that the Bank will still give you the note's face value in return for it, which isn't the case in any other country. A hand-written note from 1705, for example, would have been made out for a very specific amount of money and if you presented a note for ninety nine pounds, seven and four pence, that's exactly what the Bank would give you... in new money. The alternative, however, is to take the note to Barnaby Faull, Director of Banknotes at Spink. Here Barnaby would cast his expert eye over the note and give you its probable value at auction, possibly into tens of thousands of pounds.

"I'm the sort of person who, if someone comes into the office with a really good banknote, will actually tell the owner it's really nice. You've got to feel enthusiastic about what you're dealing in or else you can't buy and sell it," says Barnaby. He must be fairly enthusiastic about banknotes as he's been dealing in them for thirty eight years, and working for all that time at Spink, the famous company which auctions and deals in coins, medals, stamps, bonds & shares, wines and books as well as banknotes. He doesn't collect banknotes himself, of course; there would naturally be a conflict of interest. But he certainly understands the way collectors work.

As a child in Sussex Barnaby used to collect sixpences to put in a cardboard album made by Sandhill Bullion. "The coins used to tarnish in the board, but that didn't matter," he says, "I can remember that the 1952 sixpence was very rare and I had one, which made me so pleased. The point is that you look for the date that you're missing; it's not the money, it's the thrill of the chase for a collector. They're single-minded and I can understand that." These days Faull is more of a collector of collectors; his decades at the most reputable dealer in banknotes has given him connections with clients all over the world "When something really interesting comes in you don't think 'What can I sell it for?'" he says, "You think 'Who am I going to offer it to?' It's all built on human relationships."

|

And the banknote market is absolutely a collector-based market rather than an investor's market: "If someone came to me with a hundred thousand pounds and said, 'I want to buy the best bank notes you've got,' we couldn't sell them any. When a good banknote comes in, we know just the collector that would love to add it to their collection, so we would always place it with a passionate collector, rather than an investor. I advocate buying because you actually like the note, rather than for its prospective value. There is no room for investment money because there aren't enough banknotes, and there are plenty of pure collectors to buy everything there is."

A Venerable History

Barnaby's advice is if you like it, buy it; if you don't like it, don't. During his time at Spink he's seen the level of interest in banknotes evolve into what it is today. He began his career in the coin department after leaving school, having worked there during the school holidays. When the existing banknote expert left, the MD simply said, "Get Barnaby to do the bank notes," and so a career was born. "We used to sell a few bank notes at the end of a coin sale back then," says Barnaby, "and now we sell coins at the end of a banknote sale; it's a big and growing business."

Although they had been used in China and the Far East since the seventh century, the first English banknotes appeared in the seventeenth century, made out for precise sums, and in the eighteenth century fixed denomination notes gradually appeared. Before that time everybody just used coins; they didn't trust paper. However, during the Napoleonic wars the Bank of England worried that people would hoard gold so the one pound banknote was introduced. Among the notes close at hand in Barnaby's office is the fourth one pound note ever produced, "We've sold number two in the past," explains Barnaby, "number four is right here, number three is in the Institute of Bankers... and we've no idea where number one is. Probably in the back of a book somewhere!"

As we look through these very old, and very large, notes, some of their fascinating history is literally written all over them. As well as signatures and scrawls, some notes have been cut clean in half. They were deliberately cut in half by the bankers or the notes' owners. This was to enable one half of a note, or batch of notes, to be sent to its destination in one stagecoach, and the other half in another stagecoach, meaning that any highwayman who held up one of the coaches only came away with a bundle of no-good half notes. They weren't valid until the two halves were stuck back together again at their destination, with the serial numbers on both halves matching. Which sounds a damn sight safer than some of the internet banking which goes on these days.

Interest in notes themselves has grown, according to Barnaby, over the past forty years. "People have collected coins for two thousand years," he says, "and every household has a drawer full of old coins from holidays and so forth. But you wouldn't hang on to a foreign note; it's too valuable - you'd change it back to sterling at the bank. But when you think about it, a banknote is twenty times the size of a stamp, it's much better printed because it has to be to stop someone from copying it; an interesting one in good condition is instantly going to interest a collector."

Barnaby shows me the oldest watermarks on some of the eighteenth century notes, and explains that the notes we use today are printed on paper still made by the same company in Hampshire as was used two hundred and fifty years ago. No one has ever stolen the paper; it's probably kept more securely than notes are even at the printing stage, he says.

"The only time they had a problem was when the Germans made notes during the war in an attempt to destabilise the pound; the largest counterfeiting operation in history," Barnaby says. "It was called Operation Bernhard. At a prisoner of war camp Jewish forgers were made to produce very, very good forged notes, but they didn't have access to the watermarked paper. There's a tale that goes that there was actually an imperfection in the authentic notes' watermark, which in their efforts to make a perfect note, the Germans corrected. The story is that they made a perfect note... but it was too perfect to be authentic. I would love to believe that because it's such a good story."

Characterful Collectors

The other thing Barnaby's been collecting during his time at Spink is some fantastic stories. There was the chap who came into the office with a whole bundle of hundred pound notes from the 1930s which, when they were printed, would have each bought a couple of terraced houses in Battersea. "He'd found about forty of these notes in a safe in Jersey and left them with us to sell. Within the bundle there were about eight thousand-pound notes he hadn't noticed. Each of those would have bought you a house in Belgravia in the '30s. A thousand pound note is now worth about twenty five thousand pounds at auction; a house in Belgravia... well, I dread to think!"

There was the time Barnaby had to buy (for a period of 12 hours) the entire contents of the lockable duty free cupboard on a grounded aeroplane in order to leave a client's collection in a safe place overnight when he was required to disembark for the night in Bombay but couldn't take the collection with him through customs.

Then there was the man who bought a piece of antique furniture in the back of which he found about five banknotes which went on to sell for two hundred and fifty thousand pounds. And the elderly gentleman who brought in an album of Zanzibar notes printed by a company called Waterlow whose archive had been destroyed by fire. "This chap came in with a collection of notes which he'd been given when he was a boy; presumably one of his relatives was connected with the production of the notes. It was an extraordinary collection which he decided to sell and give the money to charity. We catalogued and auctioned it for him and it went for about a hundred and seventy thousand pounds; he was sitting in the room as I did the auction, completely agog," enthuses Barnaby. "The whole thing was great fun. That's the human side of things."

Cashless society

And what of the future of the bank note? I ask if Barnaby thinks we're heading for a cashless society. "I think we probably are heading that way. It drives me bonkers to stand behind someone in the queue paying for a croissant with a credit card, but people do use them all the time. Cash is quite an old fashioned thing. In the future we'll have a card that we just swipe every time we buy something. That would be very good for the banknote market, of course, because people will get nostalgic about them."

In the meantime, the sheer variety of work done by Spink's banknote expert is keeping life very interesting. When he's not chugging on the train from Southampton Row to his home in Wiltshire, he's jetting around the world to visit clients and Spink's overseas offices. "It's nice to be doing an English provincial collection one minute, going to Penang to do a Chinese collection the next and then awaiting the arrival of another Chinese collection from Buenos Aires shortly. The notes are moving all over the world."

But as he goes about collecting collectors and their stories, Barnaby reflects that, "It's a strange old business if you think about it; people buying stamps or coins or banknotes. It's a personal foible; these things are intrinsically worth nothing at all so why should people pay so much for them? But because I used to collect, I understand it. You either have a collecting gene or you don't."

|

Provincial Pieces

English provincial banknotes offer a unique and fascinating insight into the historical development of the English banking system. The David Kirch Collection which will be sold this autumn is a remarkable link with the past

The extent of the David Kirch Collection of provincial banknotes is incredible. Two large boxes full of carefully wrapped notes, divided into their counties of issue. And Barnaby Faull is delighted, "The provincial bank series is a fantastic one," he says, "and very few people know it exists."

Until the mid-eighteenth century the majority of private banks were located in the city of London but by 1798 there were just over 300 country bankers. Wealthy people outside a 30 mile radius of London could open their own banks and they were known as 'country' or 'provincial' banks. The banker's aim was to confine his notes to the immediate locality, where they would be recognised and trusted, and hopefully remain in circulation for a long time. Once outside the vicinity, the notes would gravitate to his London agent for redemption.

In 1825 a crisis occurred which saw the collapse of many private banks. A major factor was the over-issuing of notes such that they could not be honoured if a number came in for payment together. The collapse of one or two banks caused a run on the others and general panic set in. There are numerous stories from this period about the ruses used by the banks in an attempt to allay the panic, including banks employing a number of people who would come into the bank one after the other and 'pay in' amounts of gold coins, which would immediately be taken out the back and brought around for the next 'customer'.

The Bank Charter Act of 1844 aimed to eliminate note issue by all except the Bank of England. Only banks issuing on 6th May 1844 could issue after that date. Somewhat surprisingly, this was the first time that the government, which had controlled the minting of coins for hundreds of years, had attempted to regulate the production of bank notes, and by 1921 the last provincial note issue had ceased.

The notes in the David Kirch Collection form a veritable A-Z of the country; from Abergavenny to the Yorkshire Banking Company, towns and counties alike are represented. I rifle through the Dorset section with Barnaby, pushing past a number of Dorchester and Lyme Regis notes to get to Shaftesbury and find a very beautiful note issued in my home town. He's right; I never knew it existed.

"You don't have to be a bank note collector to be interested in these," explains Barnaby. "I was born in Sussex, I'm part-Cornish and I live in Wiltshire; I'd be interested in owning notes from any of those counties. I look at some of the local bank notes I'm cataloguing at the moment and think how lovely they are.

"Many of the banks went bust, and all eventually closed; because of that people ended up with valueless notes in the back of old drawers, so many of them have turned up over the years. I'd love people to be more aware that you can get hold of these notes with the name of your local town on them.

"The owner is selling the collection on behalf of the David Kirch Charitable Trust so all the money raised will go to charity, which is very important to Mr Kirch. He's gone as far as he can with this series; he's come full circle and now it's time to sell. Generally speaking provincial notes cost from about a hundred to six or seven hundred pounds. They're very affordable."

The most beautiful are works of art, the more crudely printed ones, and those with bankruptcy hearing stamps and handwritten notes on the back are rich in history, and all of them very desirable.

The David Kirch Collection will be sold at four auctions around the country starting with a London sale on 2nd October and continuing in December and early 2013.

|

Above: A £5 Sudbury Bank of Alexander, Birkbeck, Barclay & Buxton note. It has a vignette of a building at the centre, a design of circles at the left and is printed in a distinctive orange-red colour. Each of the four partners listed on the note was a well-known member of the Victorian banking world. The name of 'Barclay' is perhaps the most recognisable name for us today. In 1896 the Sudbury Bank was one of 20 private banks that combined to form Barclays bank.

|

Above: A very rare unissued £10 note from the Wiltshire and Dorset Banking Company for issue at its branch in Warminster, date 18- (c 1835-1883), black and white, with the bank building at left. Very rare and in exceptional condition. It is estimated to fetch between £400-600 at auction.